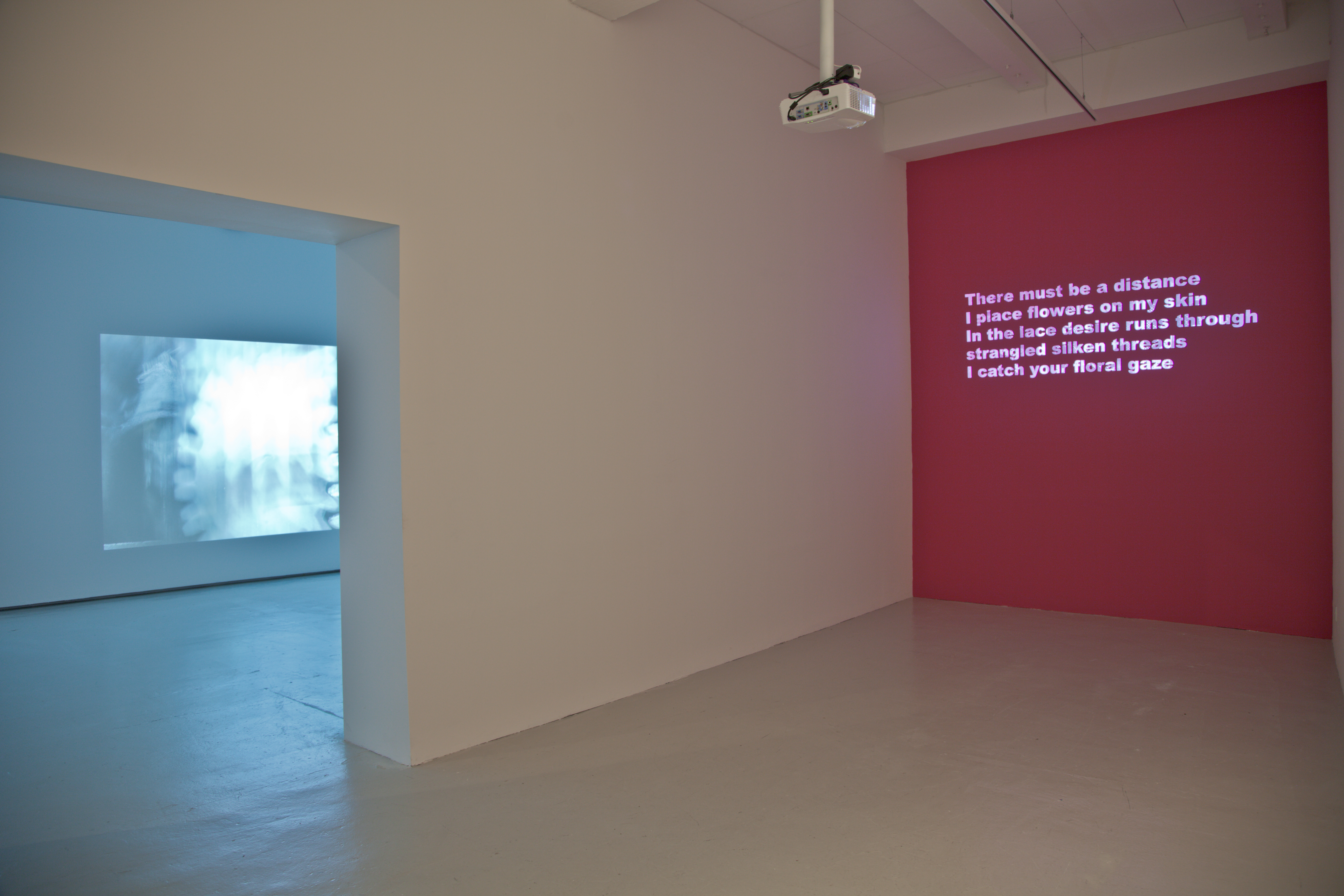

The video installation June’s lace is a triptych. You will presumably hear the sound of the work before you get a visual impression: a throbbing, piston-like infernal mechanical sound that makes sense when you connect it with the two green metal looms in the two outer projections that flank the calm sanctuary in the middle in the form of a lace curtain. What we see are English power looms hammering out the finest lace, faster than any experienced human lace-maker can.

The two outermost images show these eternally working machines, the middle image is more like a rest for the eyes. The projection shows a lace curtain in front of a window in which car headlights are reflected. Whether we are outside looking in or inside looking out is hard to say.

Before industrialization, lace was something fine, something exclusive and special. But with the advent of the machines, lace could now be bought by the yard for very little money; and in time it didn’t have to be made from raw silk, but could be made of polyester or some other inexpensive synthetic textile. This devaluation meant that lace became something anyone could own, and its social esteem sank. Lace curtains appeared in all ordinary homes as something that could symbolize order and prestige, but which in reality could quickly be interpreted as precisely the petty-bourgeois urge to seem finer than one was.

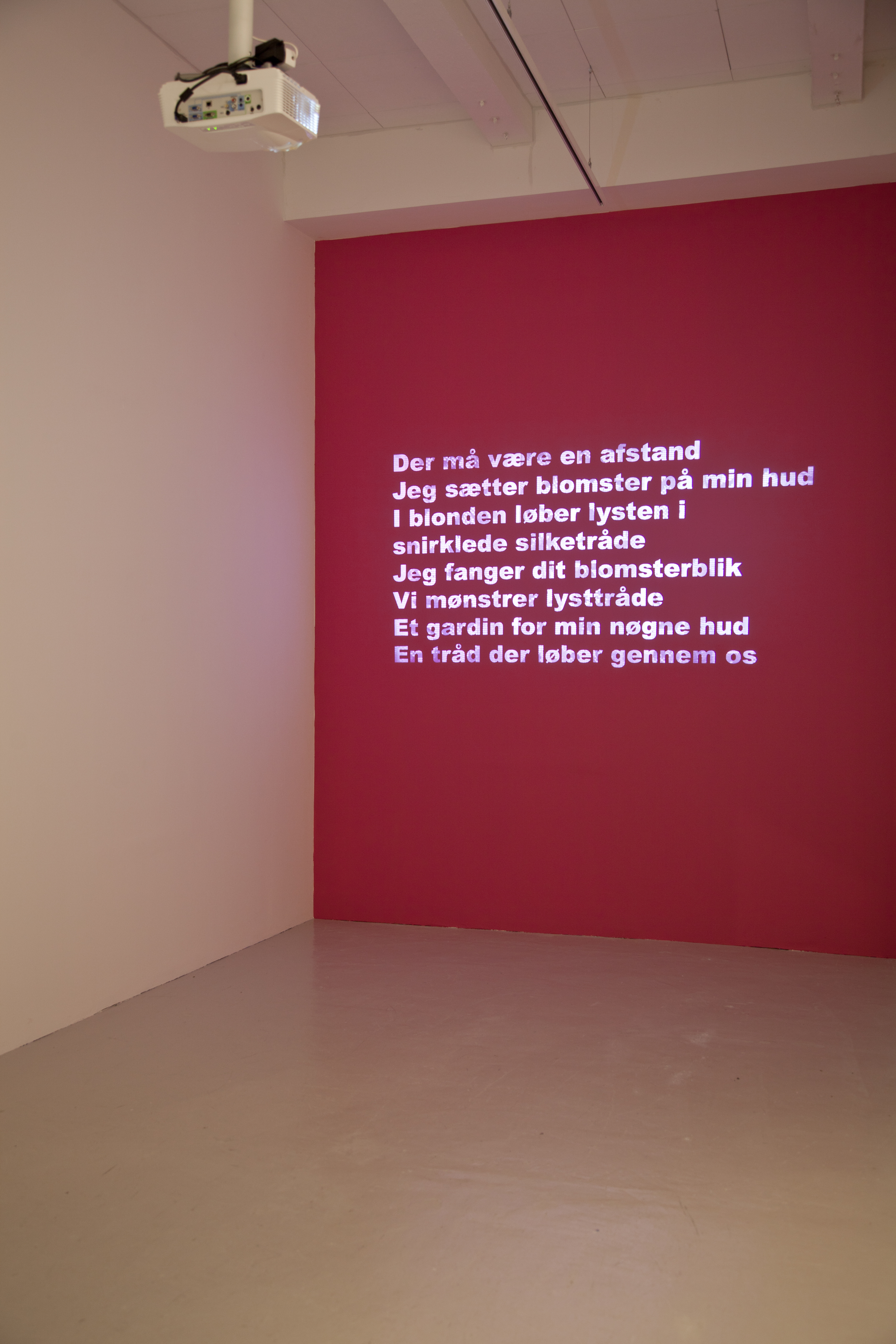

Running parallel with this more social reading of the lace curtain, there is a more existential interpretation, a narrative of the magic of the veil, of humanity’s need for an extra protective layer between itself and the world. And a poetic story of lightness and beauty, of the feminine urge to decorate and ornament, of the joy of seeing a piece of cloth waving in the wind.

On the gable outside Brandts Klædefabrik Eva Koch has projected various pieces of lace in the large format. This lace functions as a membrane between an outside and an inside. Visually there is an alternation in one’s ‘position’ between outside and inside the gently undulating curtain.